A cheese by any other name

Australian farmers breathed a collective sigh of relief when Trade Minister Don Farrell declined to sign a free trade deal with the European Union (EU) in October.

Back in Australia after trips to Japan, China and the United States, Mr Farrell says an agreement to “continue talking” was the most positive thing to come out of discussions with EU counterparts while he was in Osaka for the G7 Trade Ministers’ meeting.

Beforehand, he had warned a deal was not certain, despite more than five years and over a dozen rounds of negotiations.

“I have made it very clear Australia will not sign a deal for the sake of it, and I meant it,” he said in a statement.

Mr Farrell previously walked away from negotiations at EU headquarters in Brussels in July because of a disagreement over meaningful market access for Australian agriculture, including beef, sheep meat, dairy products, sugar and rice, much of which are subject to tariffs and quotas.

Mr Farrell says it was made clear to EU representatives that the offer received in July wouldn’t get the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) over the line, especially when it came to beef and sheep meat quotas.

“I had been hopeful that when we met them in Osaka, that we would have received a better offer,” he says.

“We needed a significantly better agricultural offer. And when that didn’t come, I took the view that we hadn’t made sufficient progress, and I couldn’t recommend to the Australian people that we sign the deal.”

Another major sticking point continues to be the EU’s insistence on Australia giving up the right to use the names of products that originated from Europe.

Known as Geographical Indications (GI), they’re intended to protect against misuse or imitation of the registered name within the EU and in non-EU countries that agree.

The EU claims GIs establish intellectual property rights for those products, although some are the names of plant varieties or styles, not places or regions.

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade website lists 166 foods and 234 beverages the EU seeks to protect as GIs in Australia.

But Mr Farrell says he hopes the issue can be solved to the satisfaction of Australian farmers and producers.

“We had made it clear all along that for Australian producers who had left Europe post-World War II, that these names like prosecco, feta, parmesan, weren’t just economic issues,” he says.

“They were also cultural issues; they were a way of these Australians keeping a connection with their homeland. And I think at the end of the day that started to sink in with the Europeans.”

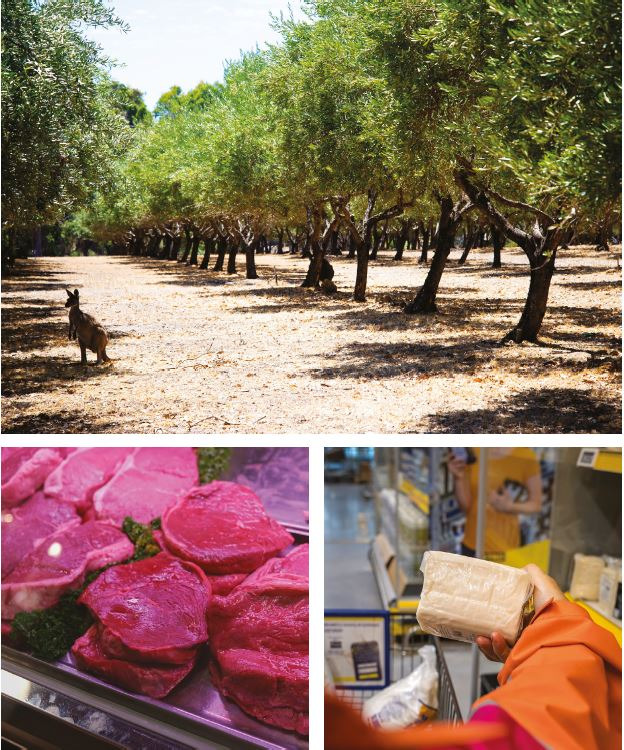

A NO-GO ON NEGOTIATIONS Top then clockwise: Aussie olive grove; packaging cheese; Red meat for sale. Trade Minister Don Farrell declined the deal offered by EU representatives, citing quotas, production conditions and market access as major setbacks when it came to an equal and fair agreement. Photos: Supplied

NO WHEY

Bega Valley dairy farmer Phil Ryan says he’s grateful to Mr Farrell, and Agriculture Minister Senator Murray Watt, for refusing to sign the deal.

“We were concerned a number of weeks ago that broader pressure might cause the government to sign it in its present form,” he says.

“I haven’t yet seen anything compelling for dairy at all. The key part is that restriction on Geographical Indicators is really just a thinly veiled excuse for trade protectionism and anti-competitive action.”

Mr Ryan, who is NSW Farmers Dairy Committee chair, says the proposed restrictions on GIs would stop the Australian dairy industry using terms such as feta, haloumi, gruyere and a range of other cheese names.

“The estimate is that it would cost us $75 million a year in lost revenue, and the compliance burden would be placed on our government, so it would be an additional cost to taxpayers as well,” he says.

“European Union farmers are already heavily subsidised, with 30 per cent of their income from government assistance and incentives.”

Mr Ryan says the EU exported 70,000 tonnes of dairy products to Australia each year, compared to Australian exports to the EU of 500 tonnes.

“It’s a very unlevel playing field as things stand,” he says.

“And then to further restrict our ability to use those terms, which aren’t necessarily geographical indicators. Feta for example, is a style of cheese making. It’s not specific to a region.”

Mr Ryan also expressed concern about the EU enforcing GIs through the back door by negotiating FTAs with Australia’s trading partners that prohibit them from buying Australian products labelled with European GIs.

This includes New Zealand which signed an FTA with the EU in 2022 and gave up the right to use the name feta.

Another condition of the NZ-EU FTA is that only Italian prosecco will be able to be sold under that name in New Zealand from 2028, despite the country being the biggest importer of Australian prosecco.

According to a National Farmers Federation (NFF) fact sheet, the average EU tariff on Australian agricultural imports is 14.2 per cent, with dairy tariffs the highest at 32.3 per cent, followed by sugar (27 per cent) and meat (19 per cent).

MEAT OF THE MATTER

Braidwood beef producer Peter Grant – who is a member of the NSW Farmers Business, Economic and Trade Committee and represents NSW Farmers on the NFF Trade Committee – says the EU had the potential to become a valuable market for Australian red meat, “particularly for the premium end of the market”.

“From a red meat producer’s perspective, the offer wasn’t good enough and you’ve got to keep in mind what other commodities are facing as well,” he says. “What we don’t want to see is a situation where one commodity is a winner and other commodities are a loser – it really needs to be a balanced deal across all commodities.”

Mr Grant says he was supportive of the government’s work in negotiating an FTA, but he wasn’t disappointed when Mr Farrell didn’t sign the deal that was offered.

“I’m not privy to the actual details of what the offer was, but from what I’ve heard, we were being put at a disadvantage to our competitors, such as Canada and New Zealand,” he says.

“So really, why would you sign on to an agreement that puts you behind your competitors from the start? It’s much better not to have a deal than have a bad one.”

HANGING IN THE BALANCE

Despite the latest setback, Mr Ryan and Mr Grant agree it’s important to continue negotiations with the EU to improve the terms of the FTA.

“There are highly desirable aspects to free trade, more generally speaking, but for dairy at the moment, the way this agreement is drawn up, it’s very, very one-sided,” Mr Ryan says.

Mr Grant says it’s in the interests of both the EU and Australia to have a better agreement than what was tabled and he had hoped common sense would prevail on quotas, production conditions, GIs and market access.

Mr Farrell says Australian representatives were ready, willing and able to participate in further talks which could take place in early or late 2024.

The main hurdle will be elections for the European Parliament due to take place in June 2024.

“We don’t simply want to repeat the same exercise,” Mr Farrell says.

“The closer it gets to the mid-year elections in Europe the less likely it is that we can progress anything. And then of course, after that election, you have a new group of people to deal with. Will they be pro free trade or anti free trade?”

If that’s the case, it has been suggested negotiations will most likely restart in late 2024 or after the next federal election, which is due between August 2024 and May 2025.

SNAPSHOT

• European Union GDP: $US16.6 trillion (2022)

• Population: 445.7 million (2022)

• Two-way trade of goods and services: $AU97 billion (2021-2022) Source: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade website

NAMES TARGETED BY THE EU

• Dairy: Feta, Gorgonzola, Grana Padano, Gruyere, Haloumi, Parmesan, but not Camembert, Brie, Gouda, or Edam

• Olive oil: Kalamata

• Smallgoods: Chorizo

• Spirits: Grappa, Irish Cream

• Wine: Prosecco